In recent years, microservice architecture has taken the lead in most software solutions, and in many cases, it is most often chosen as the architecture from which we start development. However, it’s worth asking yourself whether this is always the optimal choice. Moreover, if you choose microservices as a set of rules you want to stick to, are you sure you are aware of the consequences of this choice?

In my opinion, microservices offer two main benefits:

Unfortunately, in most cases when microservice architecture is chosen, the team ends up creating a so-called “distributed monolith”. If at the beginning of work, you rely on dependencies between services or DB, and in the end, you deploy 90% of services simultaneously, you should admit that it would be easier to do it as a single deployment unit. It would reduce the effort related to the implementation, automation, and maintenance of microservices, and allow you to focus intensively on business problems.

Long story short, you have to remember that the microservice software architecture style is not simple and carries a lot of technological complexity. Don’t crack a nut with a sledgehammer! Running a Kubernetes cluster for one application or service doesn’t make sense, because the costs of infrastructure and all configurations will exceed the costs of development. There are other “simpler” cloud solutions, e.g. AWS ECS, AWS Fargate, AWS Beanstalk, or even EC2 + simple Load Balancing (other cloud providers have similar solutions).

Below are some heuristics that can help you decide which architecture to choose.

| What do you need? | Microservices | Monolith |

| Independent implementation units | Yes, but only with good logical separation | Yes |

| Simple and quick to build infrastructure | No | Yes |

| Dynamic scaling | Yes | No |

| Business logic autonomy | Yes – if we divide the domains correctly | Yes – if we divide the domains correctly |

| Dynamic horizontal scaling of specific system components | Yes | No |

| Technological autonomy | Yes | No |

| Independent development teams | Yes | No |

| Quick project start (development kick-off) | No | Yes |

The term “monolith” is often used as a synonym for legacy applications. By properly designing a monolithic application (appropriate selection of internal architecture), you can definitely shorten the development kickoff without excluding possible changes in the future. And you can still transition to microservices. This is where the modular monolith approach – or, in particular the “monolith first” approach – comes in handy. If you don’t know what scope the project will have in the coming years, and you don’t know how fast it will grow, then starting with a well-structured monolithic application may be a good idea.

What does the Modular Monolith offer?

Of course, there are many other factors that may affect the choice of system architecture. However, taking into account the ones I mentioned above, it might be better not to start the project with an assumption it’ll be based on microservices. If you’re not sure how the whole system will look like in 2–3 years, it’s usually better to go for the modular architecture. You start with a well-planned monolith, and then – if needed – gradually transform it into a modular monolith.

You should also remember about the available, simple solutions that don’t require system architecture at all – such as serverless solutions, AWS Lambda, etc. They can work well in the case of relatively simple, not overly complex problems.

At Pretius, we focus on long-term projects and a long life cycle (maintenance and development), which is why sustainability and expandability are usually very important to us (but of course, your particular case might differ). The choice of system architecture often boils down to the method of deployment and, consequently, the infrastructure where the system is launched.

However, from the perspective of software developers, infrastructure and application deployment are slowly becoming secondary topics – there are specialists with dedicated positions (e.g., DevOps engineers) who make important decisions and take care of these problems. We simply want the system to be well-maintained, work without problems, and don’t incur technological/business debt. For that to happen, we need to focus on the application code.

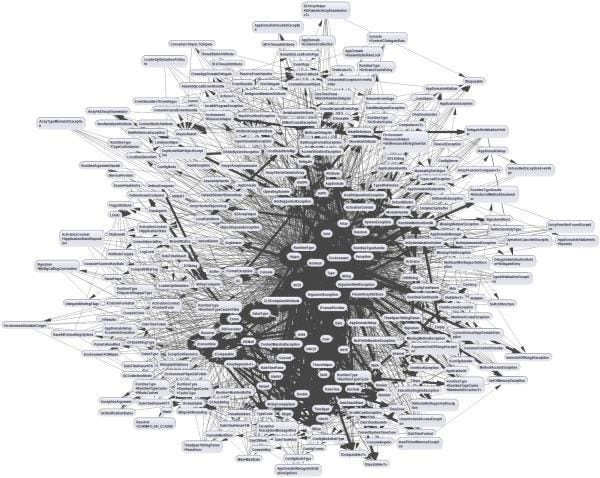

Once you decide on the system architecture, it’s time to focus on the architecture of individual applications. Unfortunately, most projects are based on layers (n-tiered architecture). In the case of complex projects, the end result is usually the same → Big ball of Mud (example on the screenshot below).

Image source: Medium.

It’s not a bad choice for simple CRUD apps or a few/dozen services, but when you try to put complex logic into such a scheme, it quickly turns out that the network of dependencies starts to cause serious problems. It’s a good idea to be aware of the existence of different styles and get to know them in more detail.

Application architecture styles:

It is worth adding that you can mix and match these styles. You don’t need to fixate on a specific solution, but simply choose tools that’ll make your life easier. This also applies to system architecture. For example, if it turns out you need to create a larger (e.g. monolithic) application in your microservice system, then you shouldn’t try to force it to fit into the microservice architecture. Instead, choose the internal architecture, divide it into separate modules / business domains, and therefore reduce the costs of DevOps/configuration work.

You can also try to find a middle ground while choosing architecture. To be perfectly honest, no such thing as the “golden middle” exists – but you can get close. Before choosing a specific architectural style, it is worth collecting some metrics about the designed system. The more information you have available, the more reliable your decision will be.

A shallow system is easy to recognize because its user interface fully reflects the structures in the database and in the application code (→ CRUD). There are no complex integrations or complicated algorithms. The main characteristic of deep systems, on the other hand, is that a number of operations invisible to the user – more or less complex – take place from the moment of user interaction to the final effect. A Google search engine or a system for processing leasing applications are good examples of deep systems.

It’s hard to talk about the principles of selecting architecture – “heuristics” that can direct us to a specific choice seem to be better term.

For shallow, uncomplicated systems developed by a small team, you can choose simpler architectures, e.g. layered and monolithic applications. However, when you know from the beginning that the complexity will be high, it will be a project for years and will require the work of large or many teams, the appropriate division of applications will be crucial and we will strive for separation of responsibilities. This can be achieved both in the microservice architecture and in the previously mentioned modular monolith. There are also technical aspects that must be taken into account when choosing a specific style.

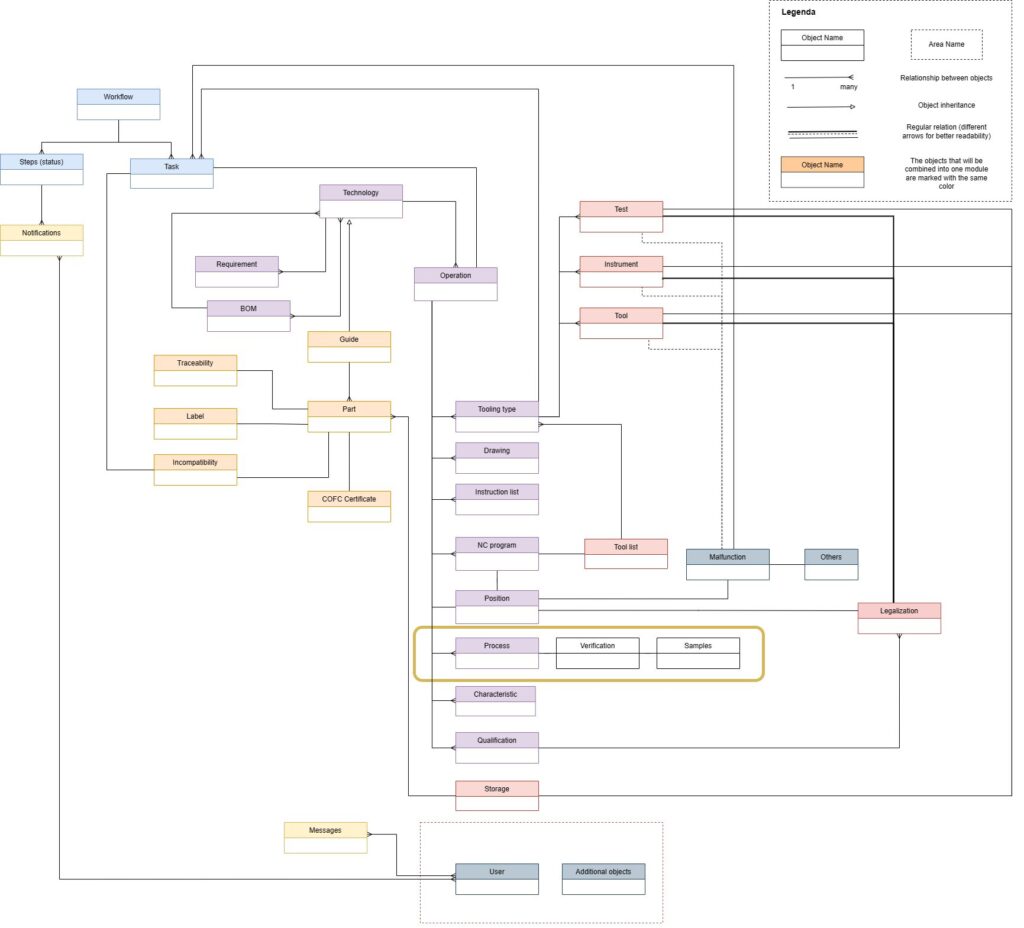

Good old brainstorming – or its newer form, event storming – are some of the tools you can use to create an initial outline of modules/services. The purpose of such exercises is to form an initial outline of domains – or lack of them – in a given business. Then, you should be able to estimate the size of the system. Below is an example of the first outline of domains/modules after analyzing the object diagram (marked with colors).

The database model is often neglected when teams choose the architecture for their project. They divide the services into smaller or larger ones, they run them in the cloud, and they build the entire envelope related to the production of microservices, but they still design the database as if it were part of a large tangled monolithic application. It’s not a good approach – if you decide on microservices, the database needs to reflect the logical division that you used on the application layer. Service binding at the database level is one of the major problems in modern microservice architectures, leading to the Big Ball of Mud (shown in one of the images above) and subsequent maintenance difficulties.

If you cannot afford separate databases per service, the division into schemas is enough to start with. Schemes will also work in modular monoliths. When it comes to the data layer with microservices, you should take advantage of the opportunities they offer – namely, you should match the database type to the business model, and not the other way around. With a little effort, everything can be flattened to a relational model, while the freedom of microservices architecture allows us not to do so.

A common way of designing a database is to create structures based on the data we need to collect (e.g., based on information received from the client). It is a good exercise to try to design a data model based on the functionalities that the application must fulfill. The resulting model is usually much “thinner” than the original assumptions, and it turns out that it is fully sufficient.

We’ve used the MyBatis tool to communicate with the DB during many Pretius projects. This allows you to maintain 100% control over what’s happening in the database, but it also has an often unnoticeable side effect – Anemic Domain Model. Writing complex SQL statements often discourages developers from creating complex relationships within the model on the side of the application code. Another consequence of that is a departure from the object-oriented programming paradigm (lack of encapsulation, logic in services).

Pretty much any developer can learn and handle solutions such as MyBatis (and other alternatives, like Hibernate, for example), so they’re very much worth considering. However, they’re just tools, and they won’t release you from the obligation to think about the side effects and consequences of your decisions.

When it comes to communication in the microservices architecture, the Asynchronous By Default approach is preferred, but you certainly can’t fully avoid using either REST or some other synchronous form of communication (gRPC, SOAP, etc.). Technology is one thing, but there are more important questions you should ask yourself. Why do you communicate? Are these REST calls necessary? Has the logic been properly separated into another module/service?

Often, microservices become a network of mutual connections – to put it figuratively, everything talks to everything. This is usually a consequence of bad division/decomposition into domains and is already a serious indication that you have built a distributed monolith and not microservices.

This problem is not just limited to communication at the level of applications/services. You have to remember that the same rules apply at the code level – Services, Facades, Classes, or packages. In both cases, it is worth familiarizing yourself with the concept of Low coupling, High cohesion. Communication in the technical context is usually not a problem but distributed transactions, sagas, compensations, and fallbacks (which are sometimes a consequence of distributed architecture) are. This is an area to focus on.

A few patterns for communication in distributed systems which you should know:

The structure of the project should be closely related to the selected system and application architecture. Apart from the components that should be common, for example, as part of DevOps requirements (applies to system architecture), the internal structure of the application itself will be determined by the selected application architecture.

Apart from architectures, in order to maintain better readability of the code in a business context, you can use the “package by feature” approach. The idea is to place code grouped within packages for a specific domain/functionality/area, and not – as is usually the case – divided into technical packages. i.e. controllers, services, mappers, etc.

Also, to be perfectly honest, I don’t recommend creating application skeletons that can be re-used within the company. There are free tools, such as Spring Initializr, which you can use to create such a project outline in a few seconds, so it’s better to consider each case independently. Copying something from other projects can lead to technical debt from the very beginning – since you don’t even check if there is a newer/better option available.

However, once you choose a structure, it’s a good idea to stick to it throughout the project in order to maintain consistency and transparency.

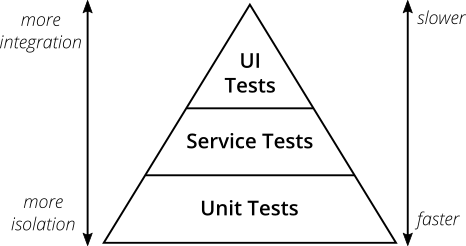

Image source: Martin Fowler.

The testing pyramid (screenshot above) is not fully applicable in the case of distributed architectures. In addition to testing within one implementation unit, you must ensure testing at the interface between these units, because you have to assume that such communication will be present. So, in addition to standard integration tests between modules/services, you can also use Contract Tests as part of API testing between modules (additional information on that is available here).

Also, the testing pyramid will look different depending on the module. In the case of shallow modules (let’s say CRUD) it doesn’t make sense to do all kinds of tests, because, in the end, you’ll simply be checking the same thing several times – the main difference will be how you invoke the tests. For deep, complex modules where the business logic can be complicated and extensive, unit tests are the way. Integrating modules, on the other hand, will necessarily require more integration tests than unit tests. Testcontainers is a great tool for integration testing, and if you want to know how to use it to great effect together with Liquibase, check out my previous article: Testcontainers + Liquibase: Make integration testing easier.

The distributed (microservice) architecture will require an appropriate method of collecting application logs. Services can exist in a production environment in many instances and run on completely different physical machines. As a result, logging into the server and manually searching logs in text files becomes time-consuming, and sometimes it may even be impossible. The solution to this problem is to implement a centralized log store, such as a document database in which logs from all applications included in the system will be collected using auxiliary tools. In addition to the centralized log store, you might be interested in using data replication tools that help you keep the data consistent (and available across distributed systems).

The market standard for implementing the requirement described above is currently a set of three tools:

The specific database and log visualization tool will depend on the project. The two most likely options are mentioned in the points above.

The diagram below shows a simplified flow of how logs from websites/applications go to the database engine.

You can integrate with Logstash via the REST API, which allows you to use it regardless of the programming language used in the application. If it is not possible to integrate the application directly with Logstash, it is possible to use the Beats tool responsible for downloading logs from text files, parsing them, and then sending them to the Logstash tool.

You can integrate with Logstash via the REST API, which allows you to use it regardless of the programming language used in the application. If it is not possible to integrate the application directly with Logstash, it is possible to use the Beats tool responsible for downloading logs from text files, parsing them, and then sending them to the Logstash tool.

One of the consequences of using a microservice architecture is quite high technological complexity. Applications are distributed on many physical machines, the system may include dozens of applications and various supporting components. Therefore, a very important aspect in the maintenance of distributed systems is their continuous monitoring, i.e. checking the condition of the system. Thanks to this, when we notice a malfunction or system error, we are able to shorten the reaction time as much as possible.

Paradoxically, in order to control the growing complexity of architecture, we need to implement even more tools that will help us in this.

The same tools are used for all types of metrics and alerts and can be integrated from any programming language.

Applications are often built in a layered architecture. By this, I mean a technical division into packages of the following types: controllers, services, a model, etc. In the code, the model is usually a simple mapping of a DB column to fields in POJO (no relation, only reference by ID). Business logic, on the other hand, is fully implemented in “services” packages. Such a division is not wrong, but it can work a bit worse in large projects.

N-tiered architecture problems:

Here are a couple of different approaches you can use instead of tiers:

The logical division at the level of system architecture is not the end – we often forget about the separation in the applications themselves. Rarely does one website equal one functionality. You should also separate domains, and subdomains (there can be many of them) that together form a specific service or application. The principles of communication between them should be similar to those used at the system architecture level: fixed APIs, interface communication, encapsulation, etc.

The offer is usually made by a different person (or team) than the one who takes care of the implementation. Because of this, it’s worth engaging a third party for quick validation of the architecture proposal at the bidding stage. Cross-checking will definitely pay off, regardless of your experience.

First of all, it’s worth checking whether the architectural design is not overkill considering the client’s needs. If you start with microservices as your first idea, you can easily choose something way too complicated. For example, you need to design one, rather small application (one domain, several functionalities), but you match it with a microservice architecture launched on Kubernetes, with the ELK stack, monitoring, etc. Do you really want to do something like this with one application, if you don’t know what the plans for future project development are?

You may also encounter the opposite situation – your proposition will be insufficient for the client’s needs. It’ll probably happen less often because in the offers everything is usually planned with solid margins – but if it does, you’ll need to find good arguments to support your approach. Also, it’s a good idea to limit yourself to the system architecture at the offer stage and leave the application architecture for the implementation stage.

What if we gave up on microservices and a year later it turns out that they are needed after all? If you build a monolithic application with appropriate structure and division into domains and sub-domains, changing the architecture shouldn’t require a revolution – it’ll simply be a natural transition you can carry out without too much effort.

Decisions in these areas will strictly depend on the client’s requirements – it is difficult to define the rules of conduct. Some elements to pay attention to:

Regardless of the type of system architecture you choose, the application should be able to handle the traffic specified by the client and be ready for possible “unexpected” spikes. You have to be careful not to fall into the trap of “premature optimization”, but if you already have specific requirements, you have to adjust the solution to them from the very beginning.

Some things to consider:

The best scenario is when the client is able to define specific metrics regarding the performance of the system such as the number of logins per hour, X visits to a specific website within X time, 10 processed lease applications, 100 searches for offers per minute, etc. Based on such metrics, you can prepare appropriate tests, and properly adjust the system.

There are two aspects to consider here:

As you can see, a modular system can serve as a good alternative to microservices or the traditional monolith architecture. Each of the approaches has its benefits and limitations. Which should you consider for your project? This will depend entirely on the nature of the system you’ll be working on. To make this decision a bit easier, consult the following tables that summarize the main advantages and disadvantages.

| Microservices | |

| Advantages | Drawbacks |

|

|

| Monolith | |

| Advantages | Drawbacks |

|

|

| Modular Monolith | |

| Advantages | Drawbacks |

|

|

Analyze your needs, talk to your trusted team members, and choose the architecture that’ll serve the project best – not just today, but tomorrow, and even many years into the future.

At Pretius, we’ve got more than 15 years of experience in building scalable software solutions for big enterprises. So, if you’d like to consult your ideas, make sure to drop us a line at hello@pretius.com or just use the contact form below. Initial consultations are always free.

Also, if you need more information about design and architectural patterns, here are some sources you can read:

Here are answers to popular questions regarding modular software architecture.

The microservice architecture offers numerous benefits such as native cloud support, physical separation of modules, horizontal scaling, loose coupling, deployment autonomy, technological autonomy, smooth CI, and multiple team collaboration on independent or loosely coupled components.

The modular monolith combines some aspects of the monolith and microservice architecture.